Spontaneous Speaking in the new MFL Curriculum

Recently I went to a really interesting session led by Rachel Hawkes at ALL Yorkshire hosted by the amazing Eva Lamb at King Edward VII School in Sheffield. I wanted to share some key takeaways and some thoughts and ideas that sprung from conversations I had over coffee with MFL colleagues and my own thinking afterwards.

Rachel is passionate about the changes (for good) that the new MFL GCSE (for first examination in 2026) will bring and she communicated this with conviction. One of the most important changes, and one which should herald a significant change to the way MFL teachers have been teaching and preparing students for the GCSE speaking exam, is that most of the new speaking exam will be unprepared. Yes, there will be some planning time for the role play and the visual stimulus, but significantly there will be two follow up interactions after the read aloud and the visual stimulus that are described as ‘unprepared conversation’ and ‘unprepared interaction’.

For many years, going back to the old speaking exam before it changed in 2018, many teachers have prepared students to learn off by heart a presentation and a series of pre-prepared questions, that has become ever longer and ever more complex. It is now common practice to give students a set of questions for each theme, often with model answers for a grade 4/5 or grade 8/9, ask them to write their own, mark them, sometimes even record them on their phones or other devices and send them away to learn them. Much of KS4 lesson and homework time is devoted to this. Many students doing the foundation paper find it incredibly hard to memorise even a few of these, don’t fully understand what they’re saying anyway, and become very demotivated as they don’t see the point in it. The students aiming for higher grades are better at memorising set answers, but even they often don’t fully understand what they’re saying and can easily omit a crucial verb or other word from an otherwise fluent, flawless sentence!

High Frequency Phrases

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with learning very high frequency phrases that can be used in a variety of contexts like je suis allé/fui/ich bin gegangen and c’était/fue/es war to give an opinion in the past tense. These are incredibly useful and should be learnt off by heart and their structure can be unpacked later. It’s the over-rehearsal of long, complicated answers that don’t reflect real world conversations and interactions, and which cannot be independently generated, which should no longer be part of our pedagogy.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with learning very high frequency phrases that can be used in a variety of contexts like je suis allé/fui/ich bin gegangen and c’était/fue/es war to give an opinion in the past tense. These are incredibly useful and should be learnt off by heart and their structure can be unpacked later. It’s the over-rehearsal of long, complicated answers that don’t reflect real world conversations and interactions, and which cannot be independently generated, which should no longer be part of our pedagogy.

So what will be needed is a sea change in how we plan speaking tasks for students, and develop students’ ability to take part in, to begin with short, and then increasingly longer, unprepared spoken interactions.

As Rachel says,

“As long as the language of these interactions is planned and based on prior learning of language from the wordlist, using the target language in the moments between tasks as well as in the tasks themselves is a central part of practice, not an add-on.

And we know from the GCSE Subject Content that the expectation is that students’ language production should be ‘clear and comprehensible’ – this is not the same as ‘fluent, accurate, fast, complex’. There also seems to be a bit of confusion about what ‘spontaneity’ means. It doesn’t mean ‘spoken without hesitation’ or ‘speaking faster’. This is more akin to ‘fluency’. Speaking activities that promote spontaneity involve contingency: both the speaker and listener need to process both form and meaning to complete the task – i.e., it can never be irrelevant what the other student has just said!

It is extremely important to remember that speed and accuracy often decrease when speech is produced spontaneously. This is important because it is the crucial complement to introducing the requirement for speaking to be unprepared and unrehearsed. We should be able to have confidence that expectations for spoken proficiency will be appropriately matched to the increased requirement for interactions to be unprepared. We should see this reflected in the new GCSE mark schemes. So, in the classroom, the sort of speaking we need to be practising is unprepared sentence creation, building from individual words in unrehearsed situations, and the sort of output we are aiming for is ‘clear and comprehensible’.”

We considered some different types of speaking tasks that are popular in MFL classrooms and the key takeaway is that not all speaking tasks are of equal validity. Rachel recommends thoughtfully analysing the task before setting it (given that we have such limited curriculum time we must make the best use of every minute). She suggests asking ourselves the following.

Four suggested production task analysis questions:

Four suggested production task analysis questions:

In short, an acid test question Rachel asks teachers to consider is whether it is possible for students to complete a speaking (or writing!) activity without any knowledge of the language. If the answer is ‘yes’, she recommends task re-design!

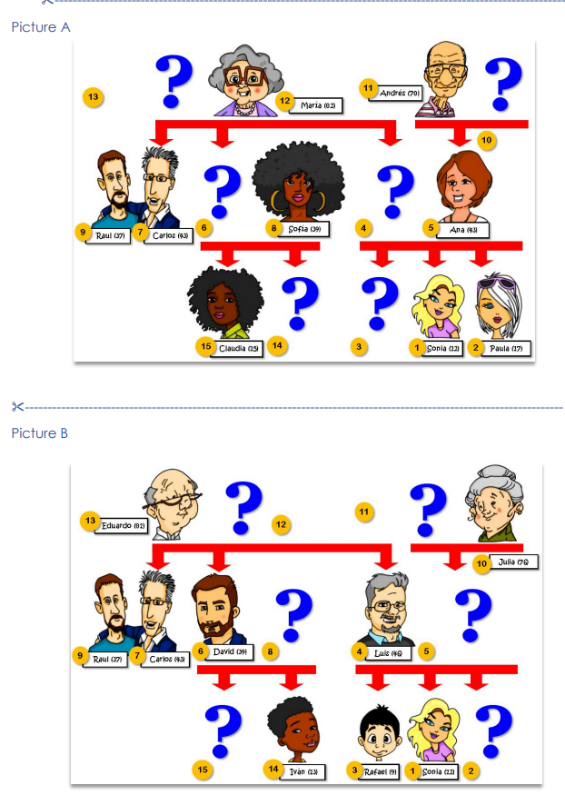

Valid tasks that come to mind are information-gap tasks, which I remember being taught about by John Trafford during my PGCE at Sheffield University in 1995, so, what goes around comes around. I remember creating these sorts of activities where students had to give and receive directions to different places based on a map, where they had to ask for different items in a shop or café and so on. The NCELP Spanish jigsaw activity is another example. Quiz trade would be a valid task as students need to translate a sentence either to or from the target language. Perhaps it could be developed such that it is a question that the other student must answer too.

The idea of ‘desirable difficulty’ (Suzuki et al., 2019), whereby learners are compelled to process meaning and form drawing on their own linguistic knowledge, has been around for some time, and has recently often been referenced on #edutwitter. This type of processing effort, it has been found, can improve long-term memory and performance (Bjork, 1994; Bjork & Bjork, 2011). However, compared with other teaching methods or strategies, building in desirable difficulty can initially appear to slow learning down, prioritising spontaneity over fluency, and this should be remembered in the context of speaking tasks. It needs careful thought so that students are in the ‘zone of proximal development’ (sometimes called the ‘struggle zone’ by teachers) – where they have to think to retrieve language and/or make key language choices, but without the task being impossibly difficult. This requires good knowledge of the range of abilities and needs within a class as the task needs to be carefully planned, then adapted and pitched appropriately.

Spanish Jigsaw Activity Courtesy NCELP ©

Using Modern MFL Technology Help With Spontaneous Speaking

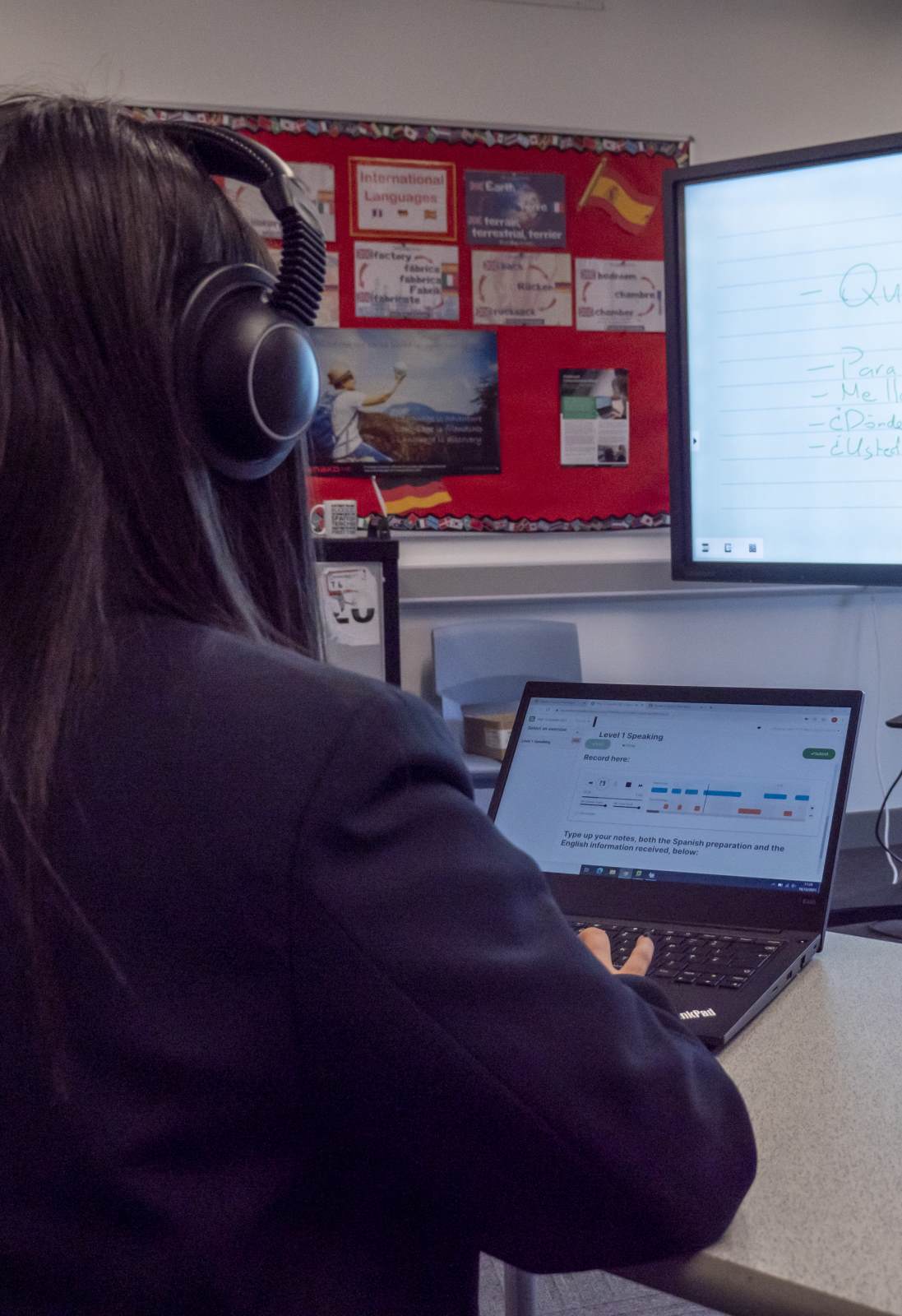

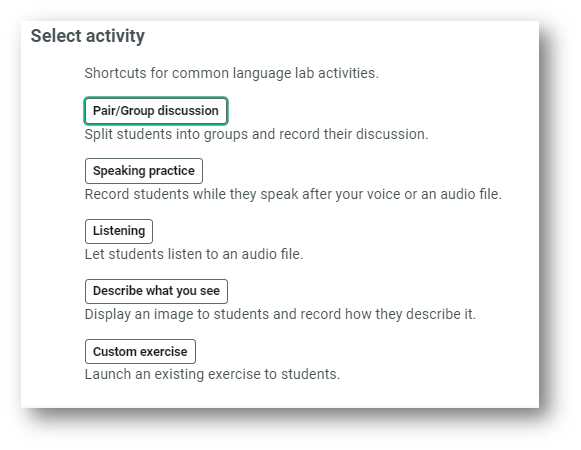

The Sanako Connect software can support the teacher’s ability to assess unprepared speech in pairs. So the teacher can launch a Pair/Group discussion, and either randomise who students work with or chose carefully who works with whom.

The Sanako Connect software can support the teacher’s ability to assess unprepared speech in pairs. So the teacher can launch a Pair/Group discussion, and either randomise who students work with or chose carefully who works with whom.

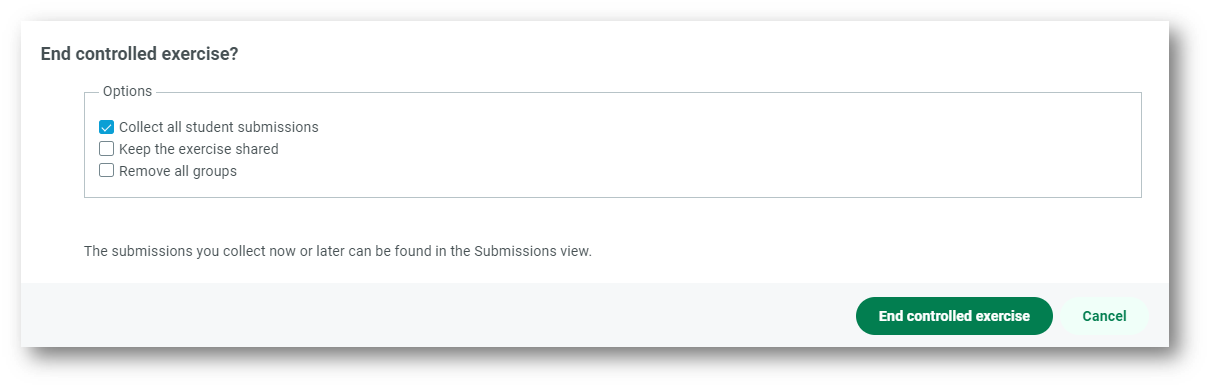

Students can then work together, doing for example an information gap activity, and when they have all recorded their answers into their device (PC/laptop/tablet/iPad/phone) the teacher can click on ‘collect all student submissions’ and can collect and mark them.

It's an efficient way to assess students’ unscripted talk regularly and the teacher can provide feedback individually either in writing or recorded by the teacher (for example you can model items that were mis-pronounced).

Teachers can provide feedback using the ‘Advanced recorder’ exercise and right click on each utterance (shown in pink). A little speech bubble appears, which, when the student clicks on it, they will be able to hear or read the feedback.

As the EEF says (https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/teaching-learning-toolkit/feedback), feedback redirects or refocuses the learner’s actions to achieve a goal, by aligning effort and activity with an outcome. It can be about the output or outcome of the task the process of the task the student’s management of their learning or self-regulation. This feedback can be verbal or written, or can be given through tests or via digital technology. There is strong evidence that it can add at least 6 months to students’ progress.